|

Those mountains which at least possess the merit of being beautiful belong to the number of gods whom we are beginning not to worship. Their thunders and avalanches have ceased to be for us the fulminations of Jupiter; their clouds are |

no longer the robe of Juno. Henceforth we can fearlessy invade the high valleys, the abode of the gods whither the genii repair.... A rustic poet invited for the first time to visit a royal castle, asked permission to ascend the throne for one moment. No sooner did he find himself there than the dizzy sensation of power took possession of him. He saw a fly flitting beside him. "Ah! I am a king now; I will crush you!" and with one blow of his doubled up hand he stretched the poor insect upon the arm of the gilded chair. |

"THE HISTORY OF A MOUNTAIN" - BY ELISÉE RECLUS

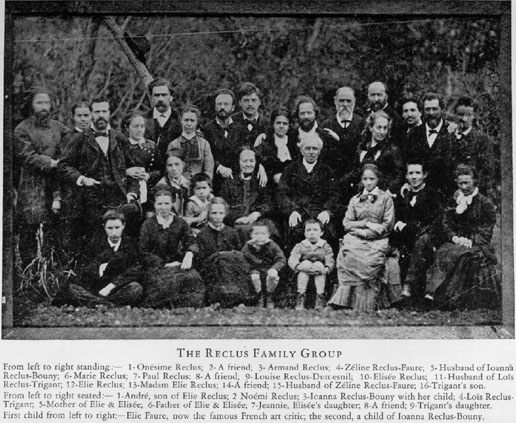

REATNESS was the note of Elisée Reclus' life. It appears in all he did, conspicuously in the thought which planned, and the indomitable energy which completed, "The Universal Geography." This, his great work for the world, is in every respect monumental. Man, it is said, is a microcosm of the universe, and every individual a microcosm of man. Most men, however, are but partially so, and this is especially true of the most noble and the most ignoble. David was a more complete representative of humanity than Marcus Aurelius or Mazzini, but he was not so god-like. Now, Elisée Reclus belonged to the greater order of men: he was a man sui generis- one whom the pagans would have made a demigod or hero.

REATNESS was the note of Elisée Reclus' life. It appears in all he did, conspicuously in the thought which planned, and the indomitable energy which completed, "The Universal Geography." This, his great work for the world, is in every respect monumental. Man, it is said, is a microcosm of the universe, and every individual a microcosm of man. Most men, however, are but partially so, and this is especially true of the most noble and the most ignoble. David was a more complete representative of humanity than Marcus Aurelius or Mazzini, but he was not so god-like. Now, Elisée Reclus belonged to the greater order of men: he was a man sui generis- one whom the pagans would have made a demigod or hero.![]()

We must not, therefore, expect to find in him any of that littleness, that weakness, which, while it often excites anger and contempt, is sometimes so attractive and endearing, because in the sinner we see a man on a level with ourselves. Still, there was in Elisée Reclus what some may consider a touch of human weakness. While to those who claimed superiority of any kind he could be terrible in the scathing contempt or mocking bitterness with which he spoke, to the unhappy--the moral failures- he was gentle and much-enduring.![]()

If we ask what was the most impressive feature of his life, it was not its indefatigable toil- many an agricultural laborer stood on a level with him here; it was not the wealth of knowledge he acquired, and which he freely poured out on the world- others have acquired like fortunes and have spent them munificently; it was not the social ideal which he formed and which inspired his life, because there again he was not peculiar; it was not the lofty nature of his intellect, nor the faithfulness of his affectionate heart, nor the indomitable energy of his will; but all these things combined together and forming a unique character. And no one who beheld its manifestation could help feeling that he was in the presence of a great soul.![]()

More than fifty years have passed [1905] since I first came to know Elisée Reclus. Wishing, with some other friends, for private lessons in French, we were recommended to Elisée Reclus, then a fugitive from the tyranny of the Coup d'Etat. He came, a small picturesque figure in a hooded cloak: his pale face, beautiful blue eyes, lofty forehead, all were noted; but they were as nothing compared with the impression he made upon us by the knowledge and soul which appeared in all he said. ![]()

I recognized in him a real teacher- the first in any pedagogical sense I had ever had. My mind was peculiarly prepared for his influence, being, as I was, the spiritual offspring of 1848. I believe my teacher was the same, since I cannot find out that he was interested in revolutionary ideas before that period. He often spoke of the agitations of that marvellous dawn, stormy day, and most unhappy sunset. It was then the hard winter of revolutionary hope, and there was little that could be said that was not sad and discouraging. But the whole matter and manner of his teaching combined to awaken mind, to stimulate thought. To be with Elisée Reclus was to drink in draughts of moral and intellectual life.![]() Sometimes he spoke of the hardships endured by his fellow-exiles, and I pictured them with no other bed save the seats in the parks; but he never spoke of what he himself was suffering. It was only some thirty years later, when I lived in Paris and in constant intimacy with his brother, Elie, that I learnt something of what they went through in London. The lodging that he and Elisée occupied was the smallest imaginable- a mere dressing-room over the doorlight. But there must have come times when they had not even such a refuge as this, for Elie spoke of walking about at night trying to find a sheltered corner on one of the bridges.

Sometimes he spoke of the hardships endured by his fellow-exiles, and I pictured them with no other bed save the seats in the parks; but he never spoke of what he himself was suffering. It was only some thirty years later, when I lived in Paris and in constant intimacy with his brother, Elie, that I learnt something of what they went through in London. The lodging that he and Elisée occupied was the smallest imaginable- a mere dressing-room over the doorlight. But there must have come times when they had not even such a refuge as this, for Elie spoke of walking about at night trying to find a sheltered corner on one of the bridges.![]()

The last time for a period of thirty years I saw Elisée Reclus was in the old reading-room of the British Museum. I asked him what he was studying- Dynamics. What, I continued, are dynamics? He did not give me a reply such as I might have got from a diclionary, but told me that by their aid he had resolved the problem why the Germans are an emigrating people and the French are not, and he proceeded to show that difference arose from the opposite configuration of the two countries. I have found since that that which struck me more by its daring freshness than its probable truth became one of the canons of his geographical science. "Pour les hommes comme pour les eaux, c'est l'inclinaison du sol qui indique la direction du voyage," he says in his masterly introduction to the "Geography of France".

Elie came with him to England. The two brothers passed certain periods of their careers in different countries, but as a whole their lives are inseparable. During more than seventy years they passed through the same experiences, and died within a year of each other in the same city- Brussels. Few brothers in the world remain during so long a period completely one.![]()

-- -- -- -- --

Twenty years of reaction and the Nemesis came. The France that voted in favour of the Coup d'Etat had to see itself invaded and hopelessly defeated and dismembered.......But Paris taken and peace made, a reactionary Assembly gathered together at Bordeaux, which subsequently came to Versailles. Paris, resentful, declared itself an independent Commune. It was exactly the idea Elisée Reclus entertained of what ought to be the form of a true society everywhere- each social group autonomous, owing allegiance to no power but the freely agreed upon decisions of those of whom it was composed. Holding such views, Elisée was the last man to refrain from acting upon them when the moment came. The brothers joined in supporting the Commune. Elie Reclus became director of the Bibliotheque Nationale, a most responsible position under such circumstances, and, best proof of the fidelity with which he discharged it, after all the horrors of the siege and the fall ofthe Commune in the midst of the blazing wreck of many public buildings, not a book disappeared from the shelves, not a document suffered from any accident whatever. One, however, had disappeared before Elie Reclus arrived to take possession. It was a Jesuit book of great importance controversially. He told me how, immediately after he had dismissed the staff, he rushed with his own assistants to the spot where it was. The book had gone, its place was empty.![]()

Elisée Reclus, than whom no one was better fit to lead and command men, chose, no doubt on principle, to work fraternally rather than authoritatively. He volunteered into the force defending the Commune of Paris, and was, in a sortie, taken prisoner on the Plateau de Chatillon, and imprisoned at Versailles. While he lay there, liable to be tried by one of the ruthless courtmartials of the time, I received a letter from him, which, for lofty dignity, singular desire to minimize his own danger as compared to that of others, and true grandeur of soul, could hardly be surpassed. ![]()

He was transported from prison to prison some ten or a dozen times. In one, the prisoners were visited by Jules Simon, a member of the Government, his object being to ameliorate their lot. Former friends, the man in power, coming on Reclus, exclaimed, "And you, M. Reclus, I am sorry to see you here." "Monsieur," replied the proud Communard, "je ne vous connais pas." He was condemned to transportation, but on the petition of a number of European men of letters and science, the sentence was commuted to banishment.![]()

How many have rushed into the thick of the revolutionary struggle because their hearts were broken by private tragedies, or their souls embittered by persistent non-success! I blame them not; they are often the very finest and best. But with Elisée Reclus it was not so. From the time I parted with him in 1852 to his reappearance in the Commune in 1871, his career had been one of ever-increasing literary success. ![]() -- -- --

-- -- --

Hast thou given the horse strength? Hast thou clothed his neck with thunder? Canst thou make him afraid as a grasshopper? The glory of his nostrils is terrible. He paweth in the valley, and rejoiceth in his strength; He goeth on to meet the armed men. He mocketh at fear, and is not affrighted; Neither turneth he bade from the sword . . . He saith among the trumpets, Ha ! ha ! And he smelleth the battle afar, the thunder of the captains and the shouting.

But Elisée Reclus was not only capable of becoming a man of war, fearless and brave, he was an ardent lover of the beautiful, the peaceful and even the placid. Else why did he always fly to such spots as Vascoeuil, as Lugano, and the Lake of Geneva ? He himself has spoken in his "Geography" of "the placid waters of the Lake of Geneva mirroring the surrounding mountains." His fiery soul was enamoured of "clear, placid Leman." Else why did he so long choose its shores for his dwelling place? His great spirit here found Nature in the mood that gave him the deepest repose, earth's best symbols of eternal peace, and of eternal love. For Elisée's soul arrived at that point when it breathed a universal love, a god-like tolerance, a perpetual blessing on men and all created things. Without writing a line of poetry that I am aware of, Elisée Reclus was himself a living poem. (1)![]()

Thus he appeared to others; of himself he would have claimed as his greatest distinction that he was a free spirit. But the basis of that freedom was love. And opposed to love he saw law- law, the offspring of fear, of egoism, of jealousy. Against law as something which consecrated grasping selfishness, and human disharmony; against law, which bound in horrible chains those who hated each other, and prompted outraged lovers to solace their bleeding hearts with so much cash; against law, which drives men to crime, and then takes away their liberty or their lives; against all law Elisée Reclus protested.![]()

And that not only by word, but by action. Elisée never neglected propaganda by deed when it came before him as the next act which had to be done. Such an opportunity occurred when his two daughters were about to be married. The marriage laws of France were resolutely ignored, and the festival by which the two weddings were celebrated, on Oct. 14, 1882, was patriarchal and communal. As it took place in Paris, and a large hall had to be provided for the numerous guests, the antique simplicity of the mode of celebration was somewhat marred by the grandiose character of the surroundings. The Hotel Continental, with its buffet and waiters, was a little appalling, not to say depressing, but the words spoken by Elie and Elisée gave it elevation and solemnity. I and my children were present on the occasion, and I can testify that it was something so truly real and affecting that I longed for a public acknowledgement of the only one true law of marriage: "Those whom God hath joined together, let no men put asunder." ![]()

I have said nothing, or next to nothing, on the point which in most men's eyes must constitute his chief claim to public attention- his distinguished career as a geographer. But I do this purposely, well knowing that I have not the learning for the task, and assured, moreover, that it will be done most effectively by our dear and honoured friend, Kropotkin, his fellow-worker and fellow-struggler.![]()

Any sketch of his work would have shown one thing, and that is that a great idealist can also be the greatest of realizers...His justifiable resentment against modern Christianity led him at times so far that one might think him fundamentally anti-Christian.... No one could be more in harmony with the spirit of early Christianity. Jesus Christ, would, I believe, have regarded him as his brother. Elisée Reclus, accepted the absolute Truth as far as it was known to him, accepted the Life which is universal Love. I do not appeal to these things as merits, but rather as evidences of the state of a soul who, believing most profoundly in justice, truth, and love, necessarily displayed them in his life.... ![]()

RICHARD HEATH

"THE HUMANE REVIEW", OCTOBER, 1905

(I) Since writing this I have learnt that as a young man he often wrote in verse.