IN NO MODERN REVOLUTION HAVE THE PRIVILEGED CLASSES BEEN KNOWN TO FIGHT THEIR OWN BATTLES. THEY ALWAYS DEPEND ON ARMIES OF THE POOR, WHOM THEY HAVE TAUGHT WHAT IS CALLED LOYALTY TO THE FLAG, AND TRAINED TO WHAT IS CALLED "THE MAINTENANCE OF ORDER"

IGHT SURPASSES RIGHT," said Bismark, quoting from many others; but it is possible to make ready for the day when might will be at the service of right. If it is true that ideas of solidarity are spreading; if it is true that the conquests of science end by penetrating the lowest strata; if it is true that truth is becoming common property; if evolution towards justice is taking place, will not the workers, who have at once the right and the might, make use of both to bring about a revolution for the benefit of all? What can isolated individuals, however strong in money, intelligence and cunning, do against associated masses?

IGHT SURPASSES RIGHT," said Bismark, quoting from many others; but it is possible to make ready for the day when might will be at the service of right. If it is true that ideas of solidarity are spreading; if it is true that the conquests of science end by penetrating the lowest strata; if it is true that truth is becoming common property; if evolution towards justice is taking place, will not the workers, who have at once the right and the might, make use of both to bring about a revolution for the benefit of all? What can isolated individuals, however strong in money, intelligence and cunning, do against associated masses?

AS FOR US, WHOM MEN CALL, "THE MODERN BARBARIANS", OUR

DESIRE IS JUSTICE FOR ALL. VILLAINS THAT WE ARE, WE CLAIM

FOR ALL THAT SHALL BE BORN, BREAD, LIBERTY,

AND PROGRESS.

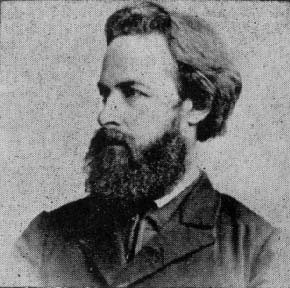

ELISÉE RECLUS

"EVOLUTION AND REVOLUTION"

ith the death of Elie Reclus, there has passed away an interesting figure who at one moment played a notable part in the world. He was one of a large family, of whom Elie's younger brother, Elisée, is perhaps the best known, alike by his great geographical works and his position as an apsotle of philosophical anarchism. They sprang from an ancient Protestant family belonging to that south-western region of France which throughout French history has produced so many daring fighters and adventurers, so many charming saints, like Fénelon, and not a few great writers, of whom Montaigne, while incomparably the greatest, is yet quite truly and genuinely typical. Here Michel Elie Reclus was born in 1827. He studied theology at Geneva, Strassburg, and elsewhere, but soon realized that he was not adapted for a theological career. At an early period he began to take an active interest in Socialism, more especially that of the school of Fourier, while at the same time he became an ardent student of sociology, of folklore, and of religious psychology. His share in the events of 1848, led to his exile, and for a time he took refuge in England. On his return to France he was a vigorous propagandist of cooperation, and he founded a Fourierist journal which had considerable success among the working class.

ith the death of Elie Reclus, there has passed away an interesting figure who at one moment played a notable part in the world. He was one of a large family, of whom Elie's younger brother, Elisée, is perhaps the best known, alike by his great geographical works and his position as an apsotle of philosophical anarchism. They sprang from an ancient Protestant family belonging to that south-western region of France which throughout French history has produced so many daring fighters and adventurers, so many charming saints, like Fénelon, and not a few great writers, of whom Montaigne, while incomparably the greatest, is yet quite truly and genuinely typical. Here Michel Elie Reclus was born in 1827. He studied theology at Geneva, Strassburg, and elsewhere, but soon realized that he was not adapted for a theological career. At an early period he began to take an active interest in Socialism, more especially that of the school of Fourier, while at the same time he became an ardent student of sociology, of folklore, and of religious psychology. His share in the events of 1848, led to his exile, and for a time he took refuge in England. On his return to France he was a vigorous propagandist of cooperation, and he founded a Fourierist journal which had considerable success among the working class.![]() When the Commune was proclaimed, Elie Reclus declared himself on its side. He was appointed director of the Bibliothèque Nationale. During those troublous days, when these most precious collections were exposed to dangers of all kinds --- bombardment, incendiarism, the ignorant hatred of social fanatics --- Elie Reclus was indefatigable; he adopted every available precaution, took measures to save the Bibliothèque from the great fire. How unselfish was his devotion appeared when, as a reward, on the restoration of order, he barely, almost by chance, escaped summary execution, to be condemned instead to transportation; he succeeded in escaping to London and again lived in exile in Switzerland and England, until the amnesty was declared.

When the Commune was proclaimed, Elie Reclus declared himself on its side. He was appointed director of the Bibliothèque Nationale. During those troublous days, when these most precious collections were exposed to dangers of all kinds --- bombardment, incendiarism, the ignorant hatred of social fanatics --- Elie Reclus was indefatigable; he adopted every available precaution, took measures to save the Bibliothèque from the great fire. How unselfish was his devotion appeared when, as a reward, on the restoration of order, he barely, almost by chance, escaped summary execution, to be condemned instead to transportation; he succeeded in escaping to London and again lived in exile in Switzerland and England, until the amnesty was declared.![]()

The Commune was the climax of Elie Reclus's career as the active propagandist of a new social order. Henceforth, although his sympathies always remained on the side of the generous humanitarian aspiration which had stirred his youth, he devoted himself entirely to those anthropological studies, more especially of savage custom, which gave him a European reputation. He lived in Paris until the period of the Vaillant bomb outrage when the police, vainly seeking his son Paul Reclus, known to be the friend of many prominent anarchists, dragged off the old man to the police station. After this unnecessary outrage, Elie Reclus left France for the last time, now a voluntary exile, and settled in Brussels. Here he was one of the founders of the Université Nouvelle, up to nearly the time of his death lecturing on the evolution of religion, and here he died.![]()

As an anthropologist, Elie Reclus was a recognized pioneer in a field which has since been brilliantly cultivated by such eminent writers --- to mention only English writers --- as Frazer, Hartland, and Crawley. His position was well recognized in England. A number of the articles in this department of the "Encyclopaedia Britannica" were from his hand, and his best book, "Les Primitifs," translated into English by Mrs. Wilson under the title of "Primitive Folk," was included in the "Contemporary Science" series. The special characteristic of his scientific work is its sympathy with the operations of the savage mind and its insight into the working of savage intelligence. ![]()

Elie Reclus was one of the first to show that savage beliefs and customs, however outrageous or fantastic they may appear from the civilized point of view, have a demonstrable reasonableness and a justifiable morality when studied in connection with their environment. His scientific methods do not quite satisfy the more exact requirements which are now made in this branch of science, but the spirit and attitude of his work is that which now marks all research having as its end the unravelling of the savage mind. ![]()

From the literary side the defects of strict method in Elie Reclus's ethnographic work were a distinct advantage. He was not only a scholar and a man of science, but also something of an artist. His literary style was admirable. He loved the rich and expressive language of the sixteenth century, and his writings show how profitably a modern man may enrich his vocabulary by a judicious study of Montaigne and the other great masters of that age. "Les Primitifs" carries no scientific authority, but it remains the most charming of introductions to the study of the psychology of primitive peoples, while it is at the same time a delighfully and intimately personal book, reflecting the author's quiet humor and grave irony, at every point suggesting his humane and profound philosophy of life.![]()

The style was the man. Extremely learned in his own field, endowed with a singularly luminous intelligence, Elie Reclus has been described as the very type of the sages of antiquity. But no man was more simple, modest, unaffected. Even those who but casually met the old man with his radiant face and the shabby coat, vaguely felt the presence of the gentleness and goodness, the universal benevolence, which had survived all the rough shocks of a lifetime. Those who knew him best loved him most; "he was a man of infinite sweetness and goodness," truly writes to me one of his colleagues at the Université Nouvelle. Although he lost his early faith in revolutionary action, he never lost his sympathy with those who suffered, rightly or wrongly, in the cause of humanity; in his little apartment in Paris, and afterwards in Brussels, men of science mingled with the outcast practical idealist of all nations. In the morning you might read in the papers how some revolutionary leader was being hotly persued by a foreign Government; in the evening you might find him in the person of some pale, silent little man sitting by the fire in Reclus's salon. For every brave word or deed, in any country, which seemed to him a blow struck for social or intellectual freedom, Elie Reclus was up to the last full of a tender, appreciative, unworldly sympathy which could never be forgotten by those who had experienced it. Of himself and his own actions he rarely talked, perhaps it seemed to him that there was little to say. He was one of those men who are ranked among the criminals while they live, among the saints when they are dead.

HAVELOCK ELLIS