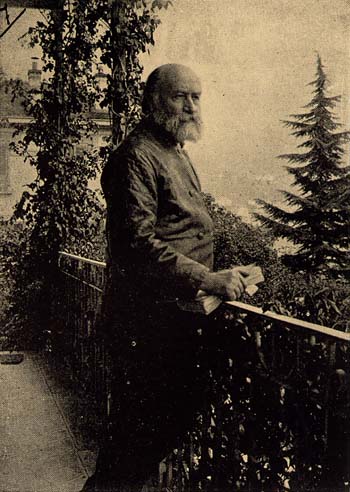

UNDAY March 13,1904, Elisée Reclus was in thee midst of us. He had come to tell us that he had appreciated our efforts, and to assure us of the interest that the constitution aroused in him, at the Château de Peuple, in a great family in which the individuals associated without confounding themselves, and dedicated themselves without renouncing themselves.

UNDAY March 13,1904, Elisée Reclus was in thee midst of us. He had come to tell us that he had appreciated our efforts, and to assure us of the interest that the constitution aroused in him, at the Château de Peuple, in a great family in which the individuals associated without confounding themselves, and dedicated themselves without renouncing themselves.![]()

All of us have engraved upon our memories the wise and encouraging words which he addressed to us on the occasion of his visit. ![]()

Elisée Reclus, likewise, retained a recollection of his visits to the Château replete with joy and hope. I had the occasion to speak to him of this visit again, at Brussels, about a year ago, and it seemed to me that there gathered upon his gentle and the same time extremely vivacious countenance, the vision of the forest of Boulogne with its foliage of innumerable shades and the exquisite variegations of its dawns and sunsets. I had read, in the eyes of the master, the happy certitude of how greatly the natural charm offered by the vicinity of the Château, would have elevated, embellished and fortified our souls. ![]()

For this man of science was also, and to a not inferior degree, an artist. His love of life, his humanitarian creed, his enthusiasm for all which is good and generous, sprang up' in his spirit, from sources of harmony, of grace, of taste. It is somewhat because of his artistic taste that Elisée Reclus scorned the filth of politics and the haughty self sufficiency of men of law and the laws themselves. A potent breath of beauty animated all his scientific and social work. ![]()

No work, is, on the other hand, more harmonious and beautiful than the entire life of our illustrious and regretted friend Elisée Reclus...![]()

The preoccupations imposed upon him by his works, the fame of which was immense, did not suffer him to abandon his libertarian propaganda. The sight of so much natural splendours, the dealings with so many men of different origin and civilization had, moreover, permitted his dream of social redemption to expand. Not one of the political agitations of his times left him inactive.![]()

In 1866 he affiliated himself with the International. "I have the presentiment that something great is going to happen in the world" wrote Henri Martin in Le Siècle a few days after the conference in London. Elisée Reclus had, not only the presentiment, but the certainty of it. Embracing with his eyes of the investigator, the entire earth, he was better prepared than anyone else to grasp the universal import of the formula which, veritable heart of the modern workingman, established that all workers are brothers and that their emancipation must be the work of the toilers themselves...

The geographer, naturally, did not destroy in Reclus, the sociologist. A friend of Bakunin and of Kropotkin, he participated intellectually in the anarchist movement and always proudly vindicated his quality of anarchist. One may cite, among numerous articles and prefaces to books, from his volume entitled "Evolution, Revolution and the Anarchist Ideal" as the faithful reflection, and in some ways the complete reflection, of his convictions on political and social matters.![]()

His social work, as I have previously remarked, is thus the complement, the prolongation of his scientific work; both respond to the same conceptions of beauty and of liberty.

The Geographic work of Elisée Reclus consists of three great works: "La Terre", composed of two volumes; "La Géographie Universelle", comprising nineteen volumes; and, lastly, "L'Homme et la Terre". In the first, the author studiesthe earth from the physical and astronomical point of view; in the second his study of the planet is extended to the observation of the multiple manifestations of the life at thesurface of the globe; in the last, finally, the life and activity of man are intimately associated with the physical milieu and the reciprocal influences of the milieu upon man, and man upon his milieu are therein particularly clarified. The first, a physical geography, the second a natural geography, the last a social geography, these three works constitute an indivisible ensemble in which is evolved the essentially classical conception of Elisée Reclus in an incessant harmony between all phenomena of nature and of idea.![]()

Before re-printing, -- he always held himself to strict account. Thus descriptions sometimes mutilated, too often imperfect or colourlesss, or discourses and journals of voyages, acquired under the pen of Reclus, a new savour, entirely special to the surroundings, of which he made survive the traditions, the customs, the veritable physiognomy, in sum, in that which it possessed of the most salient and durable.![]()

The style of Reclus, of an incomparable purity, added to the charm of his exposition of which the order is perfect. Elisée Reclus was what is called a thoroughbred writer. Fine, to the point of refinement, but without récherché, his language flows with elegance and facility, full of picturesque images, set with souvenirs or with literary evocations. It is of a precision and a nicety absolutely classic. ![]()

Here is for example, the description of a cascade, taken from the volume called "Histoire d'un ruisseau", which Reclus had written at the age of twenty-five:

"Among the cascades, what an astonishing diversity! I know one charming one, among others, that hides itself under the foliage and under the flowers. Before precipitating itself, the surface of the brook is perfectly smooth and pure; not a projection of rock, not a herb at the bottom interrupts the silence and rapid course. The water slips into a canal as regularly dug out as if it had been hollowed by the hand of man. But at the place where it descends the change is sudden. Upon the surface whence the water throws itself into a cascade, arise massive rocks, like the piers of an arched bridge and supporting itself upon large buttresses at the base besieged with foam. Bouquets of soapwort and other wild plants rise as from ornamental vases, in fractuousness of points which dominate the cascades while briers and clematis, spread out in waves attach their garlands to the projections of stone and veil the half-hidden sheets of the water-fall. The thick curtain of verdure undulates slowly under the pressure of the air which carries away with it the plunging water and the isolated bind- weeds whose extremeties bathe in the foamy eddies, endlessly trembling. The bird comes to build its nest in the foliage and balances himself upon the wave. Entirely adorned with the flowers of springtime, ornamented with fruits in summer and in autumn, the curtain suspended before the cataract half stifles its noise; one could almost believe it to be distant if the sun, darting its rays across the branches, did not, here and there, cause a diamond to sparkle beneath the verdure."

The style of Reclus, while keeping intact its melodious delicacy has become, with the years, more vigorous, more muscular. The deepest study of natural and social phenomena has perfected and consolidated in Reclus his conception of inseparable from beauty and from life...![]()

Elisée Reclus feared then, even while he admired, this same civilization to which he attributes, moreover, the rple of the renewer: he feared it because of its operation of violence and hetacombs. He detested it because it tends fatally to destroy the taste for the simple life and to compromise the natural harmony between man and things.![]()

The sociological work of Elisée Reclus, as well as his scientific work, must inevitably bear the imprint of this contradiction. As his geography often testifies to the contrast which exists between the savant and the artist, so his sociology shows how the revolutionist collides with the peaceful spirit imbued with affection. Fortunately, the man of action generally prevailed over the fatalist and nothing is more interesting than to hear this dreamer himself warn us of the dangers that the seductions of nature hold for us. ![]()

The book called "Evolution, Revolution and the Anarchist Ideal" is an eloquent defence in favour of the human personality, of which Elisée Reclus desired the formation thru the vortex of history, not with the view of replacing one set of masters with another, but with the aim of absolute individual independence.![]()

After having recalled the revolutions of the past: the Christian Revolution "whence sprang the shoots of a new religion more authoritarian, more fanatic" than the old; the reform which "removed fortunes and prebends for the profit of new power"; the French Revolution which determined the birth of a "new class of avid seekers after pleasure", thanks to which, "It is in the name of liberty, equality, fraternity, that henceforth all villianes will he committed," Elisée Reclus puts the people on guard against their own enthusiasms and foresees that "it is not enough to hear the cry: Revolution! Revolution!" in Order that they should immediately follow after anyone who desires to exploit their sufferings.![]()

"The time has arrived to employ only conscious forces, he cries and the evolutionists arriving at last at the perfect knowledge of that of that which they would realize in the next revolution, have them into the mêlée, without aim..."

In all the revolutions of the all seen two Parties present: Past, elesee Reclus has above live by their labour and that that of the men who wish to live by the labour of others. There is the class which has made reforms and has reaped the advantages of them; there is still a class which has made the French Revolution and has ex. ploited the profits of it. From revolution to revolution, according to Elisée Reclus, "the course of history resembles that of a stream arrested, from distance to distance by sluices. Every government, every conquering party seeks, in its turn, to dam up the current in order to utilise it right and left in its prairies or its mills."

But today?

The revolutionary convulsions of our days do not inspire him with confidence: "Still in our days," he affirms, "the Fourth Estate, forgetting the peasants, the prisoners, the vagabonds, those without work, the déclassés of all species, run the risk of considering themselves as a distinct labouring class, not for humanity, but for its electors, the cooperatives and their money-lenders."

Salvation, then, will only be found in the gradual augmentation of the number of men who guard their proud individuality and who profoundly feel their duties of solidarity, even in this eternal coming and going of abortive revolutions and in the midst of the infinite mass of the generations.

For Elisée Reclus, it is precisely in the proportion of these men who think and act in the plenitude of their conscience, that the degree of human progress will be known. Alas! How painful would these statistics be today and how difficult to draw.

All the same, Reclus urges us to the work, for, he added: "the period of pure instinct is passed, and revolutions are no longer made by chance, evolutions being more and more conscious and reflective."

He exhorts the workers to have faith only in themselves, and in their own forces. The support of power, and what is worse, the seeking of its support, serves only to poison the soul of the worker. How many workingmen remember that religious or Political authority has always desired to stifle the elevated aspirations of humanity. Social psychology teaches us that power must not be trusted.![]()

The contempt expressed by Reclus for the idea of authority was,absolute. It is in its name that men have committed the most execrable crimes; it is in its name still that modern society uses its marvellous tools of production and of progress in works of oppression and destruction. Thus he placed no credence in the fallacious promises of the State and openly condemned the socialists who conceived the social future under the aspect of a confusion of obligations and coercions. As the tree unfailingly bears its own fruit, so does all government flourish and grow fruitful in caprice, tyrrany, Usury, villainy, murder and misfortunes. ![]()

The class which governs, no matter which. composed of nobles, of soldiers or of functionionaries, agents of divine right or emissaries of electoral right, is of necessity an enemy to all progress. The vehicle of modern thought, intellectual and moral evolution, is that part of society which makes uneasy, which works, and which they oppress. It is that part of society which elaborates the idea, which realizes it, that part, which from shock to shock instantly replaces in progress this social chariot which the conservatives tried unceasingly to entangle among obstacles or to enswamp, in a marsh. ![]()

Elisée Reclus, marvelling at the spectacle of human suffering, which brings forth so many prodigies, will not, however, give it praise. He will not bless it, as the poet who lives within it

...la meilleure et la plus pure essence

Qui prépare les forts aux saintes voluptés.

Frightened, rather, by this continual incessant struggle which began in the forests thousands of years ago, he never tires of evoking the law of love-the only law which he accepts -which governs, according to him, the life of the world. Why have men violated this beneficent law? It would moreover be so beautiful to live as brothers! ![]()

Hope never left him. He saw proletarian cities transforming themselves little by little into immense associations of workingmen. In places where the word revolution has not yet pronounced he hears it across the sighs and the silent rears of those who suffer and who will finish by creating a revolutionary force. Repression will never succeed in oppressing the fermenting thought. The revolution draws near by reason of the inner work of conscience.![]()

The workers have no time to deliver themselves to the languors of pessimism. Everything which surrounds them speaks to them of their future and the human justice which is in their hands. It is necessary to act and to prepare the future life. Future society will be, to Elisée Reclus, a family of men who know how to limit their personal desires and to work for the common good. He is persuaded that the appropriation of the land and the factories, considered allready as the point of departure of the new social era, will result in perfect harmony among men.![]()

The workingmen coöperatives, the great industrial and comercial enterprises are, in his eyes, so many indications of a near-at-hand transformation of property and of the economic life. On the other hand, the strike, or rather the spirit of the strike taken in its largest sense, is to him, a powerful instrument of solidarity.![]()

All barriers will thus he annihilated and the human torrent will find at last appropriate courses whence its waves will spread without interruption, henceforth, the renewing element. The army, and with it, all the organization of servitude, will be disintegrated and will fall into decay. Our enemies know that they are pursuing a fatal work, whilst we know that ours is good. They hate each other and we love each other. They seek to turn history backward whilst we march foward with it![]()

In the same way as the artist, always thinking of his work has the entire thing in his mind, before writing or painting it, so does the historian see in advance the social revolution; for him it is already an accomplished thing. Is it not fulfilling itself beneath our very eyes by many and daily shocks? Not a day passes without some new adept coming to increase the revolutionary ranks.

For the ideas of justice and of liberty slowly but surely prepare their way within consciences. And the more consciences, which are the true force, will have learned, to associate themselves without abdicating the workers, comprising their number", said Elisée Reclus,"have acquired the knowledge of their own value the more facile and powerful will the revolution be.

...

Such is, in its large outlines, the social philosophy of Elisée Reclus. I will not delay in exposing the criticism to which it lends itself. We will consider today only the profoundly educating elements that it holds. It teaches men to love each other; to adore the earth which feeds them; to profess for the infinite beauty of the universe an enthusiastic and unceasing cult. Reclus was indeed right, when he rose against all attacks against nature and life. War with its carnage and its ravages, injustice with the hypocricies and perversions, of which it is the cause, are above all, just so many injuries that men have done to themselves. ![]()

It is from our own self-respect that we ought to draw the power to respect our fellow creatures and to be just toward them. Thus, for Elisée Reclus, the idea of justice as that of morality, had nothing uncertain about it, for it went back to their veritable source, which is life in all its manifestations. Acts tending to multiply life, to embellish it, to surround it with joy, are just and moral; the acts which are able to produce, on the contrary, a suffering, a diminution, or a suppression of life, are immoral. ![]()

The struggles which have mutilated human society, the competitions, the political or religious persecutions, tyrannies, conquests, crimes of all sorts, individual or collective, have strangely deformed, alas, this simple rule of human relations. The harshness of the conqueror, the despair of the victims have occasioned, in the course of the centuries, conceptions of justice and morality which estrange humanity from the life of pure joys of which it is the creator. The human personality, hemmed in by restraint, has often grown faint. In travelling over the avenue of time, we will meet it sometime abandoned to itself, in tears, vainly seeking in dreams a little assuagement of its pains. It aspires to a distant peace which will yield it that condition of tranquil and unalloyed happiness, that Nirvana of death in which it may find once more![]()

... le repos que la vie a troublé.

Why do we seek happiness elsewhere than in the splendours which surround us? Why do we no longer warm ourselves in the generous rays of the sun? Their fertile and joyous light no longer suffices us, then, since we prefer to take refuge in the shadows of doubt?

Elisée Reclus seeks, in his warm revocations to life and beauty to lift us out of the abyss; and why should we not heed the voice of this indefatigable apostle whose entire life has been a marvellous example of serenity and virtue? ![]()

We admire his efforts. We love all his immense goodness; but our admiration does not prevent us from having a legitimate distrust of the very harmony which Elisée Reclus is pleased to see in things. I am not so sure that nature always orders joy and love for us. Being vowed to the struggle, it is perhaps in the struggle itself that men must seek the accomplishment of their mission. ![]()

Elisée Reclus, I have a presentiment, has undergone, during his laborious life, oftener than he himself suspected, the fatal delights of nature against which he puts us on our guard. What must we think of the revolutionist who answered crime by pardon and who condemned violence, a judge of violence ? Before the Council of War which judged him in 1871, Reclus pushed the scruple to the point where he forebore having fired against the enemy. Can we conceive of a revolt which manifests itself only in inoffensive protestations when the offense is an attempt upon our rights, our most legitimate aspirations?![]()

Elisée Reclus passionately loved liberty, but he loved it only for the sweet satisfactions which it engenders. Now liberty does not desire a cult full of restrictions and of arrière-pensées. One must love liberty just as she is, with the joys, and also with the sorrows which spring from her. ![]()

Elisée Reclus has probably added a new strength to his doctrine in his last work, which we are not yet able to judge in its entirety, unfortunately. In effect, in the introduction of L'Homme et la Terre, he makes of individual liberty a tableau courageous and strong, "It is in direct proportion with this liberty and with the initial development of the individual", says he, "that societies gain in worth and in nobility".![]()

Therefore, we will not insist. Let us gather up our thoughts and make a garland of flowers for the memory of our illustrious and regretted friend. . .

We will not trouble the profound tranquility of his resting-place by stating how his modesty recoiled from the posthumous honours which men reserve for the masters. Let us be the inflexible rebels always against baseness, cowardice, injustice. Thus we will render our most beautiful homage to the memory of Elisée Reclus, and we will justify the word of the poet who sang of the educative virtue of the grave:

A egregié cose il forte animo accendono

L'urne dei forti.

The graves of the strong inflame strong souls for exalted things.

PAUL GHIO

PROFESSOR OF THE UNIVERSITE NOUVELLE OF BRUSSELS