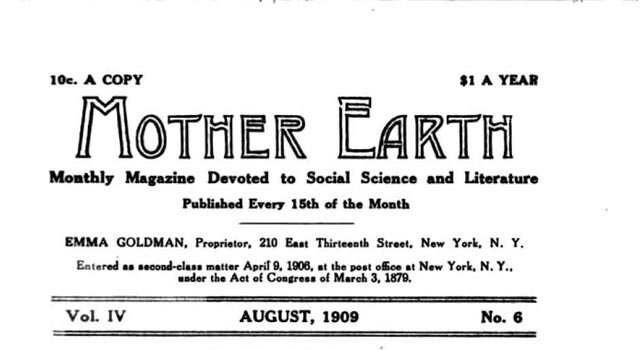

MOTHER EARTH

FREETHOUGHT

BY EDWARD H. GUILLAUME

Great word, that fill'st my mind with calm delight,

I love to feel, but cannot hope to tell,

How, like the noonday sun, thou dost dispel

The mists of error that impede our sight!

What nobel dreams, what yearning hopes excite!

What memories, too, awake at sound of thee,

Like myriad ripples on a wind-swept sea!

How full and irresistible thy might!

Thou causest to grow pale the tyrant's check;

Thou art the knell that loud proclaims the fall

Of despots and of priests, and those who seek

To crush the human mind beneath their thrall:

Thou dost avenge all wrong, make strong the weak ---

Nobility and heritage of all.

[pp. 162-5 missing]

THERE are signs of a tardy awakening in at least one direction. The police, the detectives, and all that monstrous army for which the grinding of the criminal condemnation mill means place and profit, have so overplayed their part that the storm is rising. Books such as "The Turn of the Balance" and "9009" have been published, and by their obvious veracity and tense indignation are compelling the attention of a hitherto indifferent public. Periodical literature is beginning to bristle with the subject, and this is a sure sign, for the men who make their living by writing for our magazine shave an unerring nose for the topic that is really alive.

Here and there a man escapes from prison --- one among thousands, or rather tens of thousands --- who has the capacity and the powerful position that enables him to talk, and talk with some chance of being heard. They have a man of that type in California, Griffith J. Griffith, who, as luck would have it, is a man of means, a speaker, and a trained writer by profession. He has been telling stories of his experiences in San Quentin --- the scene of "9009" --- and is making the good, easy citizens of California sit up.

They have formed a Prison Reform League there, which is endeavoring to arouse the entire country to our treatment of crime and criminals. It is issuing syndicate letters and much other literature denouncing that treatment as founded on revenge and worthy only of the Dark Ages. It is adding its mite to the exposure of the conditions prevailing in southern convict camps --- a crime of international proportions --- and is doing what it can to throw light on the mediaeval tortures applied to helpless prisoners among communities that fancy they are civilized.

Probation leagues have sprung up --- we note their formation in Chicago and St. Paul, and others may have escaped us. They voice the same general complaint: that this society is manufacturing criminals wholesale; that it is actuated solely by the fiendish policy of revenge; that its deterrent punishments do not deter; that it gives men no chance, and that so long as it continues in that folly it will be tearing itself to pieces.

We may think the work of many of these leagues and writers insufficient; we may feel that they have not yet struck the root of the evil; but they are doing a great work as stirrers of discontent. They are making people think, and to make them think is to make them disgusted with affairs as they are run at present by our unspeakable politicians and their henchmen.

We Anarchists have good cause to know how true is the proverb that when you want to hang a dog, you must give him a bad name. The literature that is being born from these prison revelations will go far toward shaking that national self-complacency which has been the hardest of all enemies to combat. A good many highly respect able gentlemen are going to get the worst of names, and the entire machinery for the administration of what, with an irony never equaled in history, is known as "Justice" is destined to find itself in the foulest of odor before many years have passed. Thus the harvest ripens, and the dawn of a new era grows brighter on the old horizon.

***

A RATHER expedient, if not ingenious, defense has been advanced by the United States Senator, who, charged with assaulting a negro dining-car waiter, justified his act by declaring, "I did not strike a man. I slapped a nigger." The judge proved his respect for the law and its makers by agreeing with the Senator. This case is by no means an isolated one. Nor is the attitude of the senatorial pugilist towards the negro exclusively southern, as some are inclined to believe. The argument that "slapping a nigger" is not "striking a man" holds good practically throughout the country. But few white people in this enlightened land have risen to the level of recognizing in the negro a fellow-man, a social equal. To the great majority a difference of color is, per se, an evidence of inferiority. Even some radicals are not entirely free from this most stupid of prejudices. And yet, impartially speaking, the spirit which sees in the colored man "only a nigger" is itself convincing proof of a mental kink, of intellectual immaturity.

***

THE recent grant of old-age pensions in Great Britain has called forth much discussion of the perennial question of poverty. As is usual, the newspaper philosophers are more voluminous than illuminative. Especially is common sense at a premium in the learned disquisitions. As to originality, it is terra incognita. Exploded theories of fatalistic, religious, pseudo-Malthusian, etc., conceptions of poverty are rehashed with an air of self-satisfied finality. None, evidently, dare analyze the vital relation of poverty to capitalist economics. One publication, however, suggests in a spirit of bantering levity, the various "possibilities" that would result if the hundred thousand unemployed of New York decided to steal rather than starve.

The suggestion may be worthy of serious consideration. What would society do with a hundred thousand "criminals" determined to eat rather than die of hunger? And suppose the unemployed all over the country were to follow the example of their New York brothers. The prisons could not hold one-fiftieth of the number. What would then happen if the poor, the underfed, the starving decided that it is as senseless as it is disgraceful to hunger amidst plenty?

They would eat and grow strong and forever forget that things are more sacred than lives.

***

THE sight of a woman riding astride has so shocked the virtuous sensibilities of a Georgia legislator that he hastened to introduce a bill, making the practice a felony. If the bill is to become a law, it will be as criminal for a woman to ride in a natural and comfortable manner as it is to live so.

The Georgia Solon is no doubt consistent. Woman cannot be suffered to discard the shackles of hoary custom that have from time immemorial kept her the submissive slave of man. Riding astride, for a woman, is an open defiance of established usage, hence immoral. Encouragement in this particular would doubtlessly lead to woman's gradual emancipation from other accepted facts. What would then become of the supremacy of men like our virtuous Solon?

***

A BRIGHT little magazinelet, Freeland, has reached this office. It contains 64 pages, the contents of which are thus characterized in the publisher's prospectus: "Devoted to economics and politics, critical in basis, libertarian in tendency, and constructive in method, favoring the largest individual development within the bounds of the law of equal freedom."

Address Alexander Horr, Station Box 2010, San Francisco, Cal.

ON PATRIOTISM

By B. RUSSELL HERTS.

THERE is a feeling in the heart of man today which has swayed the course of history for near a thousand years, which has established empires, dethroned monarchs and popes, built up continents, forced friends and families into separation; which has given birth to sorrow and rejoicing, love and hatred, cruelty, crime, and inspiration for ten centuries, and which is now one of the greatest ethical, psychological, and sociological influences upon the mind of the twentieth-century man.

Here in America is the spirit of Patriotism especially powerful, for it has been the cause and explanation of our conduct ever since the memorable days nearly a century and a half ago, when our first patriots cried out for "freedom" and "representation." It is in great measure responsible for all of our noble deeds, for our speeches, our sacrifices, our panics, bloodshed, and crimes. And through the decades as our country grew and prospered, it has grown and prospered, until today there is a kin ship of national reverence between all the Europeans, Asiatics, and Negroes within the land, and the presence of Patriotism in one's soul is taken as one of the funda mental tests of character. So far has this proceeded that he who does not hasten to rise and uncover at the opening strains of the national melody, who does not believe and claim America to be capable of all things, who does not deem it a sacred duty to go forth, if called, and crush his brother-being upon the battlefield, is gazed upon, for the most part, with fear and hatred, mingled with a touch of scorn.

In this centennial year of our greatest president, when thousands of speeches have been sounding in every cor ner of the land, when thousands more of written works plentifully decorated with the words "heroism," "Pa triotism," "American," are circulated and read in every home, is it not well to cease our impassioned declaiming, our joyous singing, even our loving reverence, for a moment, and give ourselves to the task of verifying the absoluteness, the fundamentality, the value of the glorious Patriotism which impels us to all these exhibitions?

Whence comes it? Is it eternal? And, if not, what is its cause and origin, and more especially, in this pragmatic age, why does it exist? What is its contribution to human happiness and progress?

In judging present matters, or preparing for those of the future, we have only our knowledge of the past as a foundation for assumptions. Let us review and employ what economics has taught us, and that we may reach the fundamental, let us revert to the borderland of the pre-historic.

At the earliest times which we have thus far been enabled to study, man presents himself to us in a state of what has been called "individual economy." His chief cares were the finding of food, and the securing of pro tection against the ravages of beasts, the encroachments of neighboring men, and the terrors of nature. To this stage succeeded that in which the family became the typical economic entity, when man began to realize the pleasure and usefulness of domestic life, and to protect against his enemies not only himself and his personal belongings, but also his home and all the kinsmen who gathered thereabout. Thus came the clan into being, and man's love became inclusive of his relatives.

Gradually the more civilized sections of mankind retired from their nomadic existence and settled into groups, each occupying a definite territorial district. The necessity for some scheme for the production and distribution of goods, and for the insurance of government and protection, became immediately apparent. The formation of the town or city was the result. In order to render this organization secure and powerful, it was necessary for the individual to pledge himself to protect his city in times of danger, and to assist it in the acquirement of wealth and authority. Thus was a measure of the love and loyalty, formerly lavished upon the family, transferred to the community.

During medieval times men unconsciously began to realize that geographical, linguistic, and other features contributed to render desirable the formation of larger units than that of the town. So we find extensive territories, each containing many cities, the people of which speak the same language, possess substantially the same political point of view, and dwell within certain barriers difficult of passage, each held together by the love and loyalty of their inhabitants. City warfare ceases and allegiance is transferred from the smaller to the larger group.

The nation being a recent development, it is clear that national feeling has had but a limited existence. But, it may be answered, the sentiment of which Patriotism is an outgrowth has been man's ever since we know of his presence on earth. The contention must be admitted: the quality in which we so greatly delight is directly traceable to the self-love of the savage. Broadened, extended, it is, but only because the economic unit is more embracing now than ever before. Egotism for the nation is but an extension of personal egotism, and the national selfishness which prompts a man to seek the aggrandizement of one people at the expense of another is but the descendent of primitive man's lust for power and mastery.

The world is now divided into nations, and national feeling is universally respected. Yet is the nation any less arbitrary, any more fundamental, a division, than was the family or the city? Has our reverence for the typical, temporary economic group, having passed through many stages at last reached its fixed and final form?

Let one gaze guardedly into the future and he perceives a stage beyond: a stage when material barriers shall disappear, and race hatreds be no more; when national prejudices, national egotism, national selfishness, even national love shall be swallowed up in a new spirit --- the spirit of humanitarianism, the only possible Patriotism in a state of international economy.

There is, indeed, considerable evidence that this transition is soon actually to be consummated. The improvements of the last half-century in transportation have de stroyed the importance of national geographical barriers, while the proposed universal language may remove the present national linguistic differences; the peace conferences are gradually imposing upon us a recognition of the desirability of uprooting national hatreds, while the recent advancement of such countries as Japan is teaching us the absurdity of national self-satisfaction. Moral, social, and political questions of world-significance are everywhere usurping the place in men's minds previously occupied by interest in national affairs, so that now, in the discussions of scientists, Anarchists, capitalists, unionists, Socialists, nationality is practically an eligible quantity. Many deplore this condition. To them the gradually waning sentiment is a symbol of all that is great and noble in an accomplishment of modern times. They see that Patriotism has been essential to man's uplifting, and so they insist that it is still desirable. They demand the continuation of war because, in the past, man has lost, and therefore enobled, his personality through deeds of valor. They are like those who would restore the Church to its place of power, and re-establish its tyrannies and extravagances, because long ago on account, or in spite, of these, a Bramante, a Rafael, a Michael Angelo has been nursed in its bosom. Is it their serious belief that those lips must be wet with new-sucked blood from which the breath of inspiration is to come, or that the meadows must be manured with lies and wretchedness and crime, on the produce of which genius is to be reared? Six thousand years, at least, it was, before mankind could mould a Michael Angelo; if this hypothesis were true, one might well wish six thousand times as long to pass before such another were given to the world.

But man is confident that it is not so. Religion was alone in its inspiration, the Church alone in its patronage of artists, because thought and activity were over- shadowed by these forces. Man's creative capacity demands material to mould: these themes were at hand, and all else was forbidden. It has been the same with war. So long as war exists as a significant and spectacular element in modern life, it will continue to be a theme of poets and painters. But does this import that its withdrawal will mean the death of the inspiration which gave birth to the poems and pictures which deal with war? Would it not simply signify the transference of this to another field --- perhaps to one of the many fields as yet unrecognized as fit for the purposes of art? In the work of the moderns do we not already see the puffing, plunging engine with its newly-realized harmony of creaks and crashings; the stern, pale steamship clearing the stormiest sea with perfect precision, the mud-, or soot-, or grease-begrimed laborer cognizant of the nobility, because of the usefulness, of his task --- do we not daily see these and a hundred such subjects usurping the places of the discarded topics of past decades? For the purposes of art physical strife between men has served its term --- man is moving to a music vibrant, powerful, inspiring far beyond the clash of arms.

Then there be those who tell us that, while war is waging its death struggle, nationality is a youth newly- awakened to his power. They would destroy what has become apparently repellent to them, but at the same time retain the economic and political conditions from which this has arisen. The thing is impossible. The existence of nationality signifies the continuance in each nation of the desire for its own aggrandisement. Such a competition implies conflict, and harmony is, and must be, the aim of those who would annihilate war. Conflict has existed and thrived under every state of society thus far known to history. There is but one condition conceivable to the mind of man under which war cannot exist --- that in which no final economic group is recognized.

Every change through which man has passed has made him more humanitarian: the love of family being less selfish and personal than the love of self, that of city than that of family, and the fleeting feeling of to-day a step still in advance; so that the state of internationality is the logical and natural outcome. This appears to be the final, fundamental form, for we can imagine nought be yond, Desired or repugnant to us as the change may be, it yet remains inevitable --- imminent.

We are told that as long as honor and self-respect live among peoples, so long will war persist. History itself confutes this. In the evolution of the ages even honor is subject to mutation. We remember that the abolition of duelling was opposed, and for many years retarded by the supremacy of the feeling of personal honor --- under the name of chivalry. Now we find the destruction of national duelling opposed by the appeal to national honor under the name of Patriotism. Duelling has been over- thrown and chivalry is but remembered. National duel- ling, war, will be abolished, and for the accomplishment of this Patriotism must perish. There can be only one fatherland for the man whom it is the most divine task of civilization to produce: the world; and his Patriotism will not evince itself in the stolid love of self, family, city, or State, but in the sacrifice of all for humanity!

|