|

|

| |

"Emma Goldman - A Challenging Rebel," by Joseph Ishill, (Oriole Press Bekeley Heights, 1957, New Jersey) appears in Anarchy Archives with the permission of the International Institute for Social History

|

Emma Goldman

A Challening Rebel

By Joseph Ishill

Published & Printed by the Oriole Press

Berkeley Heights 1957 New Jersey, U.S.A.

|

EMMA GOLDMAN: A Challenging Rebel

by JOSEPH ISHILL was first published in Yiddish in the

N.Y. "Freie Arbeiter Stimme" (1944.) The translation

was made by the late editor, DR. HERMAN FRANK.

It is now published in its original form.

ß Handset with the Kennerley types designed by

FREDERIC W. GOUDY.

ß The frontispiece of Emma Goldman is after a photo

taken in Paris (1928) by S. FLEEPIPE.

ß The headpiece is after a woodcut by WM BLAKE.

ß The tailpiece is from a drawing by RODERICK SEIDENBERG.

ß Colophon is from a woodcut by LOUIS MOREAU.

Summer - 1957

|

EMMA GOLDMAN

[FROM AN EDITORIAL IN "THE NEW YORK TIMES"]

MAY 15, 1940

"Anarchist" has long been a deadly word to fling about, yet the Greek philosophers of more than one school were philosophic anarchists who preferred the ungoverned to the omnipotent state. Philosophic anarchism rejected violence. Emma Goldman was connected with advocates even practicers of assassination. These acts of violence She may have regarded as reprisals.

Bitterly hated as she was in the United States, she loved it for its freedom. Esteemed an enemy of society, she was rather a searcher, however mistaken, of a society kinder to the common man. She had a quality rare among the devotees of economic dogma. She was honest. She who had had such aureate visions of revolution saw in the Soviet regime only a new form of tyranny. But it is as a personage, a character who led a passionate, stormy and variegated life that Emma Goldman lays hold upon the memory. She has denoted herself truly in her memoirs. There you see her with her flaming temper and amours, her bigotries and brutalities, her fury and her friendliness.

|

[Exclusive Edition for Private Distribution]

|

ß THE PRESENT AGE OF MANKIND IS GREATLY

ENLIGHTENED; BUT IT IS TO BE FEARED IS NOT

YET ENLIGHTENED ENOUGH . . .

ß THE TRUTH IS, that system of equal property requires no restrictions or superintendence whatever. There is no need for common labor, common meals or common magazines. These are feeble and mistaken instruments for restraining the conduct without making conquest of the judgment. If you cannot bring over the hearts of the community to your party, expect no success from brute regulations.If you can, regulation is unnecessary. Such a system was well enough adapted to the military constitution of Sparta; but it is wholly unworthy of men who are enlisted in no cause but that of reason and justice. Beware of reducing men to the state of machines. Govern them through no medium but that of inclination and conviction.

William Godwin

"An Inquiry Into Political Justice" (1883)

|

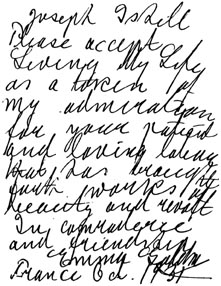

Joseph Ishill

Please accept living my life as a token of my admiration for your patient and loving labor that has brought forth works of beauty and revolt. In comradery and friendship

Emma Goldman

France, Oct. 1931.

|

Emma Goldman

n this brief essay I will try to jot down a few outstanding remarks of her life & work which played so important a role in the annals of the American labor movement as well as her great influence in the moulding of a libertarian, artistic and literary sphere of which her record stands unshaken and undisputed even by the most antagonistic and reactionary forces of her time.

ß Emma Goldman was born in Russia, June 27, 1869. The first years of her life she passed in the German-Russian Province of Courtland. When she reached the age of seven she was sent to live with her grandmother in Königsberg in Eastern Prussia where she

|

8

acquired the German language. In 1882 she moved with her parents to St. Petersburg. The name which has since been changed to Petrograd and again to Leningrad.

ß From early youth Emma Goldman tasted the bitter fruit of exploitation and hatred from her own tyrannical father as well as from Czarist hooligans from being a Jewess.

ß When she arrived in United States she was in the flower of her youth, only seventeen years old, she came with great illusions and hopes of finding a freer and more human society to live in, but instead she found more exploitation, and more persecution. On the second day of her arrival she was put to work in one of America's sweatshops. This meant long hours of toil and sweat, and abominable shop conditions in exchange for starvation wages. She was working at gloves and shawls. And here I would like to quote what Lewis Gannett, a prominent American literary critic writes in one of his articles published in the N.Y. Herald-Tribune of Oct. 24, 1931, at the occasion when her autobiography was published: 'It is for us to remember that it was not Czarist Russia which sowed revolt so deep in Emma Goldman's soul but the sweatshops of my own home city, Rochester, New York.'

|

9

ß In February 1887, Emma Goldman married, at the insistence of her family, a man with whom she had nothing in common. He was of the ordinary type, and just then Emma Goldman was going through a "tremendous spiritual upheaval." That "upheaval" was her definite conversion to Anarchism, largely due the hanging of the Chicago martyrs.

ß In 1889 She arrived in New York and associated herself first with Dr. Solotaroff, Dr. Michael Cohn, Alexander Berkman, who later in turn introduced her to John Most and they became intimate friends. In fact, it was John Most who trained her to be a lecturer and labor agitator. She spoke in the beginning before German labor circles in the German language, later among the Jewish groups in Yiddish, and awhile later she took courage and lectured in English throughout the country before various groups of mixed nationalities.

ß As a philosophical Anarchist, she became known as "Red Emma" on both sides of the Atlantic because of her constant preaching of social revolution; she always denied that she advocated violence, but from the time of the Chicago Haymarket affair on May Day' 1886, until the United States entered the World War in 1917, Emma Goldman's name was linked directly or indirectly with almost every major instance

|

10

of violence against the existing order that took place in the country.

ß After the assassination of President McKinley, Emma Goldman was arrested in Chicago and confined in the same prison where the Chicago Anarchists ended their lives. We find in Living My Life this interesting episode she so vividly and characteristically rendered analogues to her own life, when she says: 'Peculiar and inexplicable the ways of life, intricate the chain of events! Here I was, the spiritual child of those men, imprisoned in the city that had taken their lives, in the same jail, even under the guardianship of the very man who had kept watch in their silent hours. Tomorrow I should be taken to Cook County jail, within whose walls Parsons, Spies, Engel, and Fischer had been hanged. Strange, indeed, the complex forces that had bound me to those martyrs, through all my socially conscious years! And now events were bringing me nearer and - perhaps to a similar end?'

ß From what source did Emma Goldman draw her analyses and conclusions, when she was lacking the proper academic scholastics? Well, this she writes with pride and distinction, also included in her autobiography: 'More than all else, it was the prison that had proved the best school. A more painful, but a

|

11

a more vital school. Here I had been brought to the depths and complexities of the human soul; here I had found ugliness and beauty, meanness and generosity. Here, too, I had learned to see life through my own eyes and not through those of Sasha [Alexander Berkman], Most or Ed. The prison had been the crucible that tested my faith. It had helped me to discover strength in my own being, the strength to stand alone, the strength to live my life and fight for my ideals, against the whole world if need be. The State of New York could have rendered me no greater service than by sending me to Blackwell's Island Penitentiary!

ß In spite of the high ideal to which she was concentrating her life, she felt at times the weight of the pressing years and the waning lure of her feminine charm and attraction, of this she remarks touchingly and so exquisitely: 'I know intuitively that it was Maria Rodda's youth and charm that fascinated them and not my speech. [She was a young Italian Anarchist.] Yet, I, too, was still young - only 25. I still had attraction, but compared with that lovely flower, I felt old. The sorrows of the world had matured me beyond my years; I felt old and sad. I wondered whether a high ideal made more fervent by the test of fire, could stand out against youth and dazzling beauty...'

|

12

ß It would be impossible to give in this brief essay a concise resumé of Emma Goldman's numerous activities and associations with various groups and people. The files of Mother Earth under the editorship of Alexander Berkman; Die Freiheit, edited by John Most; the Freie Arbeiter Stimme, under the editorship of S. Yanovsky and other revolutionary publications of that period cover all that, or best of all one can still find in her autobiographical work: Living My Life, which is of a good size the record for any one who desires to be well informed.

ß In 1917 Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were both convicted of conspiring against the selective service draft law. Berkman was sent to the Federal penitentiary at Atlanta, and Emma Goldman was fined $10,000 and sentenced to serve two years in the Federal prison at Jefferson City, Mo. The deportation proceedings were instituted after their releases. On December 21, 1919, Emma Goldman and 247 other radicals were deported to Russia on the Army transport Bufford, known to the public as the "Soviet Ark-"

ß They were all welcomed in Russia when they arrived there, but after a short while she and Berkman were much disillusioned with the entire Bolshevik regime and in December, 1921, they fled from Russia into Latvia, and from there they began their life of

|

13

exile in Sweden, Norway, Germany, Czechoslovakia, France, England, and Canada to "settle down", but they never found the "right spot" again.

ß Only in February 1, 1934, Emma Goldman was readmitted for a short while to the United States, after 15 years of exile. Her attitude towards the government was the same as when she was deported, she spoke with the same ardent desire and convictions of her ideal, she was the same Emma of old, though a bit tired in body, if not in spirit.

ß After leaving Russia, she had this to say: 'Our old yearning, Sasha's and mine, began to Stir again in our hearts. All through the years we had been close to the pulse of Russia, close to her spirit and her superhuman struggle for liberation. But our lives were rooted in our adopted land. We had learned to love her physical grandeur and her beauty and to admire the men and women who were fighting for freedom, the Americans of the best calibre. I felt myself one of them, an American in the truest sense, spiritually rather than by the grace of a mere scrap of paper. For 28 years I had lived, dreamed, and worked for that America.'

ß My purpose in writing this short script on Emma Goldman was not primarily to give a sketchy bio-

|

14

graphical outline of her life and Struggle in the liberation of the proletariat so conspicuously known everywhere even by her antagonists: the state, church and industrialists, who feared the very sound of Emma Goldman's name; I prefer to comment here briefly on her literary and cultural aspect, the significant role she played in her distinct achievements which are known today only to very few.

ß It is most remarkable to notice that in her career as a lecturer and writer on literary and dramatic topics, she achieved that qualitative quantity whilst the most progressive and liberal elements failed in the course of many years to put across the principles of true democracy, which word they pretentiously flung in the eyes of the public.

ß It is true that the Puritanic and Anglo-Saxon literary elite did not like Emma Goldman's brand of philosophic anarchism, which in other words were the doctrine of her cult taken from William Godwin, Michael Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, yet nevertheless they attuned their ears to the sound of these ideas and little by little we began to notice that such asseverations began to creep into the columns of the daily press, in the literary magazines and books, etc., until of late the entire American literature was going through a radical transformation, towards the

|

15

progressive trend and evaluate her own democratic potentialities which were for a long time dormant and unexplored.

ß If we began to hear and read more and more about Walt Whitman, Thoreau and Emerson, it was due to a large degree to Emma Goldman's emphasizing the consciousness and greatness of their contributions towards the American arts and letters, which was at the same time also a contribution for the world at large. In the eyes of any radical thinking person such writers ceased to be Americans, but universal writers, to be understood and appreciated in all corners of the world - wherever the progressive thought found its fertile ground for germination.

ß It is known as a fact that Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, which is the exemplary unique book of American poetry was banned for many years from the shelves of any public library. The American Philistines looked upon it with shame and scorn; today it is the very symbol of pure American democracy. Thoreau's and Emerson's writings were regarded as the works of freaks and crackpots. Not so after Emma Goldman began to expand their ideas - through her continental lecture tour; in the evening she would devote her time delivering her Speeches before workingman's circles on various literary' sociologic and

|

16

economic topics; in the afternoons she was lecturing before society ladies who were perhaps more interested to get a close peep at her for a high admission price, than on the significance of Modern Drama. But all along Emma Goldman did not lose her chief purpose: to put across that which was rejected by society and by a reactionary press for a long time.

ß It was Emma Goldman again, through her initiative and personal effort that she acquainted the American public with the works of Bernard Shaw, Oscar Wilde, John Galsworthy, and others. I wonder to this day whether Shaw himself was ever aware that the fact of his recognition and success as author in this country was greatly due to Emma Goldman's own efforts in lecturing often on his plays, until her public began to demand a change on the American Stage. Until then we had mostly Shakesperian material for the sophisticated audiences and the banal comedies and burlesque shows for the riff-raff. That was not enough for Emma. Her great ambition was particularly with the modern drama and to such performed on the American stage, works of Ibsen, Bjornson, Strinberg, Brieux, Gorki, Andreiev, Checkhov, Suderman, Schnitzler, Hauptman, and others; she also, at times, undertook the management of Staging her own performances with such outstanding famous artists like Alla Nazimova,

|

17

Pavel Orleneff and others in this profession.

ß Imagine here her fortitude, her great aspiration to make a realistic form of one of her ambitions, to see that classical art performed by some of the very greatest artists the world has ever given, to see a bit of reality encased in beauty and truth, that which she so often emphasized in her lectures, now a fulfilment (sic) with her. Among other plays which were close to her heart, she chose Dovstoievski's Crime and Punishment, Ibsen's Ghosts, and An Enemy of the People. Of all the world renown dramatic artists I have seen, no one surpassed the great Russian artist Orleneff, who was actually the very personification of Dovstoievski's Roskolnikoff. This performance I will remember for the rest of my life. I have never seen anything approach in height the quality of a performance with such stark reality as this one.

ß Emma Goldman had a deep feeling for beauty and artistic expression of all arts. Most of the time she sensed psychologically such qualities without being verbose about them, but she could put her finger on the right thing when such a thing was there.

ß To exemplify Emma Goldman's interpretation of Art in Life, I will here extract a few lines from part of a speech she delivered before the Artists Guild in St. Louis, a society composed of "respectable"

|

18

Bohemians: 'That life in all its vanity and fullness is art, the highest art. The man who is not part of the stream of life is not an artist, no matter how well he paints sunsets or composes nocturnes. It certainly does not mean that the artist must hold a definite creed, join an anarchist group or a socialist local. It does signify, however, that he must be able to feel the tragedy of millions condemned to a lack of joy and beauty. The inspiration of the true artist has never been the drawing-room. Great art has always gone to the masses, to their hopes and dreams, for that spark that kindled their souls. The rest, "the many, all too many" as Nietzsche called mediocrity, have been mere commodities that can be bought with money, cheap glory, or social position.

ß Above all, she was a very good conversationalist besides being a good and spirited talker. She could tackle at a moment's notice on a multitude of subjects with great ease and without any preparation, for she possessed a remarkable memory for people and their deeds' and the contents of books that appealed to her was as ever fresh in her memory as if she had just closed the very book one was talking about.

ß And here I like to quote a few lines from her autobiography as to how she interpreted Nietzsche the man and his work, So unfortunately misinterpreted in

|

19

the days of Nazi vandalism and their twisted crazy ideology.

ß One day, as Emma Goldman relates in her autobiography, the great American critic and essayist, James Huneker, being present at a party of one of their young friends were discussing Nietzsche, Emma also took part in this conversation, expressing her enthusiasm over Nietzsche's work. Huneker was quite surprised exclaiming: 'I did not know you were in anything outside of propaganda.' Whereas Emma replied: 'That is because you don't know anything about Anarchism, else you would understand that it embraces every phase of life and effort and that it undermines the old, outlived values . . .' Then, her friend asserted: 'That he was an anarchist because he was an artist: all creative people must be anarchists, he held, because they need scope and freedom for their expression.' Huneker insisted that art has nothing to do with any ism. 'Nietzsche himself is the proof of it' he argued: 'he is an aristocrat, his ideal is the superman because he has no sympathy with or faith with the common herd. 'Then Emma Goldman pointed out: 'that Nietzsche was not a social theorist, but a poet, a rebel, and innovator. His aristocracy was neither of birth nor of purse; it was the spirit. In that respect Nietzsche was an anarchist' and all true

|

20

Anarchists were aristocrats.'

ß Emma Goldman mingled with the most shinning lights, both in the literary and artistic spheres, besides idealists, radicals, scientists, professors and even some clergymen who were sympathetic with her ideas. There is a wealth of material compressed in these two volumes: Living My Life, a magnus opus of the first water, but here also I like to quote what other critics have to say about this outstanding work of hers which is more than mere autobiography. It is, according to my estimation, one of the best historical documents of the American labor movement ever rendered in the English language; it is a concise history of the struggle of the proletariat, from the strangling of the Chicago Martyrs up to the time she was deported to Russia in 1919. I know of no other work on this subject pertaining to the labor movement that is more vividly and dramatically written. It is more than her own life, which she likes to call it. It is the Struggle of the liberation of the American proletariat towards a higher freedom that has yet to be born, which is now going on both in the factories, mines, and farms.

ß In the N.Y. Times Book Review of Oct. 25, 1931, R. L. Duffus says about this work: 'No one who desires to understand radical psychology from the date of the hanging of the Chicago anarchists in 1887 to

|

21

the October revolution in Russia in 1919 should fail to read Emma Goldman's narrative of her own life, as here given ... Miss Goldman has spent more than forty years in explaining her opinions by voice and pen. But the reader who undertakes to consider her Story as a great human narrative, which it is, should prepare himself by finding out first what anarchism is.'

ß Then further on the same writer remarks: 'The reader may be prepared to follow the story as a human document of the most absorbing interest' and he concludes: 'She is in her own right something which is rarely found, in palaces or hovels, in factories or offices or on the barricades - Her autobiographies one of the great books of its kind.'

ß It would not be fair to pass up this occasional article by omitting the fair and intelligent criticism written on the same work by one of her early disciples, Roger N. Baldwin, who today is occupying a prominent position with the Civil Liberties Union in America. I am sure that many of our friends will be in full accord with his opinion. His article appeared in the N.Y. Herald-Tribune Books Section of October 25, 1931, under the caption: "A Challenging Rebel Spirit." A more fitting title could not be more appropriate. Since the space is here limited I will quote only a few brief excerpts. This social writer, lawyer

|

22

and critic begins thus: 'Years ago when I was a youngster just out of Harvard, engaged in the then promising tasks of social work, Emma Goldman came to town to lecture. I was asked to hear her. I was indignant at the suggestion that I could be interested in a woman firebrand reputed to be in favor of assassination, free love, revolution and atheism; but curiosity got me there. It was the eye-opener of my life. Never before had I heard such social passion, such courageous exposure of basic evils, such electric power behind words, such a sweeping challenge to all values I had been taught to hold highest. From that day forth I was her admirer, though often, too, her critic; I read what Harvard had never offered me; I shared from that time on, as best I could in a reformer's jobs, the struggles of the working Class, to which her philosophy of anarchism was devoted ... She has recreated in two fat volumes of a thousand pages a life unmatched by any woman of our time. Through these pages, hot with the accounts of ceaseless struggle, march all the figures of the revolutionary movements of the dramatic years before, during and since the war in America, Russia, England ...

'For the cause of free speech in the United States, Emma Goldman fought battles unmatched by the labors of any organization.

|

23

'For an understanding of thirty critical years in the United States, Emma Goldman contributes a document which could be written by no other man or woman . . . But far more gripping than this revelation of American life or of her later search for freedom in Russia are her revelations of the inner workings of the most challenging rebel spirit of our times in these United States of her philosophy of life.'

ß While Emma Goldman was waiting for the day of being, liberated from prison, before the deportation to Russia, Frank Harris, the well known critic, essayist, lecturer and editor was supplying her with the best books from his own library and wrote her frequently letters of encouragement. He offered her any material assistance she might have wanted of him. In one of his letters to her he writes that in his estimation she was: 'A great and unerring critic. You will be out soon, which delights my soul; but I will Still be boiling in the fires of the Philistines. Why do they not deport me? I would thus save passage money.' They remained good old friends until the last days of their lives; while in France, after the World War I, they used to visit each other quite frequently.

ß I wish I could continue giving here more incidents and affirmations of her complex life, so as to form a composite picture for those who missed the chance of

|

24

knowing her in life and her work- perhaps the editor, [Dr. Herman Frank of the Freie Arbeiter Stimme who translated this essay into Yiddish] will be indulgent for this space, but before I conclude these collected fragments, I wish to quote a few more excerpts from an old article which Emma Goldman cherished above all else that was ever written about her. This article comes from the pen of William Marion Reedy, editor of St. Louis Mirror. But before I quote some of his lines, I wish for the sake of his memory, for he died long before Emma Goldman died, to give here a few introductory remarks which I find quite appropriate to extract from Emma Goldman's own autobiography. She writes; 'He and his periodical were an oasis in the desert of American intellectuality. Reedy, a man of ability, broad culture, and rich humour, also possessed a courageous spirit. His fellowship made our Stay in St. Louis a pleasant event and brought me large and varied audiences. After my departure he published in his weekly an article that he called the "Priestess of Anarchy". No finer appreciation of my ideas and no greater tribute to me had ever been written by a non-anarchist before.'

ß He begins by reviewing her first book of essays with the following words: 'Surprise of the most agreeable kind awaits people who may read Anarchism

|

25

and Other Essays. It was in jail that she learned philosophy and economics and there too she picked up a real style in writing - a style clear, direct, nervous, and often finely condenced. The woman has suffered. Yet she does not hate; She loves. She has mingled with poets, artists, thinkers, martyrs and with the outcast. She has lived with the women of the town when there was nowhere else to live. She has been accused of complicity in the murder of a President -absolutely, without justification. She has been persecuted and maltreated. No wonder that to her, a Jewess of sensitive soul, government means nothing but force, and force a sin, a crime against the free spirit.

'Her book is vivid, pulsating, flashing. It is breathless. It carries you along on the crest of a burning enthusiasm. Now you sense the pain and misery of the world. Again you note the "gesture" of some rebel avenging society and you are captivated by the eloquence with which he defends himself. And over all blows a wild, winey wind of freedom. What is Anarchy? It is freedom -absolute freedom. But how shall society organize in absolute freedom? How should she know? Let it organize according to Natare, let it develop like a tree or a flower. Faith! She has the sublimest faith in the world -faith that man will find his best only if let alone. And the faith infects you as you

|

26

read. You see the man's attempts to mould man could not have made things worse; that man his brother maims, when he ought simply to let him alone. Violence she is accused of. Her answer is: Government is violence and violence begets violence. What is a tyrant, an exploiter stricken down, compared with the thousands, the millions slain under the capitalist system? Read the speeches of Valliant and Caesario from the dock ere they went to the guillotine. They speak the Speech of a patriotism beyond boundaries, of a love beyond personal love. They are transfigured by their words into martyrs for mankind. Patriotism is a delusion fostered to keep a few people on the backs of the many. It is waste energy. It is a fetter upon humanity. It narrows the world and checks brotherhood. Prisons? They are torture-hells. They foster crime, instead of preventing it. They are filled because the few want a place to keep the many who do not recognize the sanctity of property. And they are pens in which men are held to be worked without pay for the prison contractors. Marriage is a fetter upon love. It makes form more important than spirit. Marriage is of the body. Love is of the soul. Marriage is a lie, a deceit, a crime, except when by accident and not by any law of man's making, it is a real marriage, a human sacrament of spiritual union. "All the idols are over-

|

27

throwing but always Miss Goldman submits a higher ideal to supplant the institutions she would destroy. Education? Her kind would be that for which Ferrer died in the ditch at Montjuich; no compulsion; no dogmas designed to set one man over another; no doctrines of fear; no adulation of power; no idealization of any glory but that of service to truth, beauty and freedom; nothing but the unfolding of the child's individuality under influences appealing to the idealist element in the child's nature. Woman's emancipation? It is a tragedy, for woman only wants to be emancipated into the slaveries in which men are still held. What woman wants is not man's place, but a place higher than man's - an individuality that man himself has not attained.

'And so slashes and flashes this maenad over the social, political, economic field. She sees institutions as the distortion of the things they should be. She smashes the conventions and when they crumble you see the truths that they have hidden. A rampant idealist is this terrible woman. She is terrible, for to her the ideal if realizable. She is for truth without capitulation-for the truth of Nature that man has turned into sin, for the sanctities that conventions blaspheme' for human reverences that society denounces as sacrilegious. And what she says is what everyone knows,

|

28

deep down in his or her heart, when we are honest with ourselves; only we know it for ourselves, but we feel that it would not be good if others knew it and acted upon it' Everybody is an Anarchist; he doesn't want anybody else to be one. Everyone is a Superman. Hence all our falsehoods, all our tyrannies, our greed, our vanity, our lusts.

"Without capitulation", I said this woman seeks the truth. Read her upon "Minorities versus Majorities". What says she? That there is nothing to hope from the mass. She stands with Emerson, with Nietzsche, with Stirner. "Masses! The calamity is the masses - I do not wish any mass at all, but honest men only, lovely, sweet, accomplished women only"; that is from Emerson- And she: The living, vital truth of social and economic weel-being will become a reality only through the zeal, courage, the non-compromising determination of intelligent minorities, and not through the mass". If this be Anarchy, look you to Matthew Arnold, to him of sweetness and light and say is this not his doctrine of "the remnant? "

'And this is the doctrine the police are trying to Suppress - the intelligent police. This is what Emma Goldman comes to St. Louis to preach and teach . . . Her talk, like her book, should open up here some of our hermetically sealed hearts and ossified brains.'

|

29

ß I hope this fair analysis of Emma Goldman's ideals will evoke refreshingly in the minds and hearts of many a reader of the past all that brave soul stood for, fought for and even died for.

ß In conclusion, at her 75th birthday, I want to State that there is yet a wealth of unpublished literary materials of hers which remain scattered and uncollected in the form of lectures, essays, articles, and above all, her personal correspondence which is voluminous and highly interesting as documentary material for future research work. It would be a pity that such material should in the course of time go astray or fall completely in oblivion. Someone ought to take a hand in this now before it is too late - Her autobiography does not cover all of her life. This work was published in 1931, she completed the MS. for publication in 1930 and she died in May, 1940. There remains a whole decade of her life unrecorded. A decade of her most mature life in which she kept up an elaborate correspondence with various important people throughout the world, not to mention her lectures and articles published during this period.

ß I know before she died that she was yearning for a place to settle down and do all this through her own initiative, but the cruel finality of death wished her contrarily, and here I like to conclude in her own

|

30

words as expressed in Living My Life: - 'I had long realized that I was woven of many skeins, conflicting in shad and texture. To the end of my days I should be torn between the yearning for a personal life and the need of giving all to my idea'. That was Emma Goldman in her true manifestations.

Berkeley Heights, N.J. - May 1944.

|

|

|

|

|