GOISTS that we are! In our revolutionary consecrations we rarely think of others than ourselves. We expose the griefs of the toilers, especially those of men, because men are stronger; we claim for them their right to the implements of labour and to the entire product of the labour; we demand that justice be done. Beginning to realize that we possess numbers and intelligence upon our side, we feel the desire for action springing up in us, and in the semi-consciousness of our strength we are preparing ourselves for the coming revolution. If we have felt ourselves the weaker, cowards as the majority of us are, we should still be begging for the crumbs which fall from the tables of royalty.

GOISTS that we are! In our revolutionary consecrations we rarely think of others than ourselves. We expose the griefs of the toilers, especially those of men, because men are stronger; we claim for them their right to the implements of labour and to the entire product of the labour; we demand that justice be done. Beginning to realize that we possess numbers and intelligence upon our side, we feel the desire for action springing up in us, and in the semi-consciousness of our strength we are preparing ourselves for the coming revolution. If we have felt ourselves the weaker, cowards as the majority of us are, we should still be begging for the crumbs which fall from the tables of royalty.

But under the adult, unhappy as he is, there is a being more unhappy still; it is the child. That feeble being has no rights whatsoever and depends upon caprice, benevolent or cruel. There is nothing to protect him from the idiocy of indifference or perversity of those who are its masters. Who then will raise the cry of liberty in its favour?

In our present society all authority is exercised from the master to the slave, according to a logical sequence, God reigns on high enthroned beyond the firmament and delegating his powers on the earth to the strongest, priest or king, Hildebrand or Bismark. Below come satraps of all kinds, governors, and lieutenant-governors, presidents and vice-presidents, generals and captains, masters and sub-masters, all funding their backs Wore a superior, all inflating their chests with pride before their subjects:-on one side, adoration, on the other, contempt, here, commands, there, obedience! Since the days of Jacob nothing better is to be found; society is only the rungs of ladders descending from God to the slave, and continuing even unto inferno, hells, abysses of torment, are they not the symbol of what the vanquished and the feeble have to suffer?

Among these weak ones the children are the greatest sufferers! I appeal to sincere men who recall their childhood years. Either they were themselves unhappy, or if they were tenderly nursed, if the first struggles of existence had been facilitated for them, they have seen their little comrades suffer, irremediable sufferings against which revolt is useless: what could they do against the violence and mockeries, the cowardly insults of the grown-up? Nothing, if not to amass in their own hearts, little by little, an evil treasure of vengeance which they, grown up in their turn, perhaps spent in molesting other children.

Moreover, tender as our parents might have been, devoted to the happiness of their progeny, they themselves have had to submit to the conditions which the society in which they lived have had to impose upon them, and likewise to submit their children to them. One knows how harsh these conditions are for the poor. It is necessary that the son of the famishing should enter the factory in earliest youth, that he become the servant of the formidable machine weaving wool or beating iron. Not only must he obey masters, under-masters, the least workmen, but he is also enslaved to the whole machinery of which it is necessary for him to observe the movements in order to regulate his own. He no longer is his own; every gesture in him becomes a simple mechanism; the faintest shadow of what could have been ideas is with him only an accompaniment to the monster driven by steam. It is thus that he reaches man's estate if fatigue, misery, anemia do not put a rapid end to his abortive life. Puny in body, stultified in mind, without moral ideas, what is to become of him and what are his joys? Gross and brutal sensations only awake, for an instant, but to let him relapse once more torpid, less capable of escaping from his slavery. And from time to time the legislators are occupied with regulating "child-labour in the factories". According to these laws which they vaunt as marvels of humanity, no master has the right to make the child work more than twelve hours at a stretch, or to deprive him of his night's sleep, "if it is not, however, in exceptional cases", and the exception, we know, always becomes the rule. It may as well be said that it is permissible to poison, but only in small doses, to assassinate, but only by little blows. There is your compassion, noble legislators!

But let us admit that henceforth the work of children in factories be absolutely forbidden, let us even suppose that poor parents will receive a State pension in exchange for the meager salary that the boss would give to the children. Henceforth the schools would be opened, and education ready for all, the child of the poor as well as that of the rich.

But are not the schools also shops whose mechanism is scarcely less dangerous than that of the factory? The master seizes the child and brutalizes him from the very beginning with formulas, senseless words, gestures minus ideas. Down on your knees! And the child falls upon his knees. Join your hands! And the child must pray. To whom is he to address himself? He knows not. What language does he speak? Latin. He is wound up like a top, like a spring and there he is and functions in conformity with the program. And this is called religion!

But let us suppose that the school really be laic. Well, the religious formula would be replaced by a formula of grammar, the incomprehensible Latin sentences will give place to French words which will be no dearer. Whether the child understands or not, is of little importance. It is necessary that he understands according to a formula drawn up in advance. After the absurd alphabet which make him pronounce words otherwise than they are read, and thus accustoms him in advance to all the follies which are to be taught him, come the grammatical rules which he recites by heart, then the barbarous nomenclature called geography, then the narrative of royal crimes termed history. And how could the well-endowed child at length disembarrass his brain from all these things which are made to enter there by force, in helping himself sometimes with martinets and impositions? If the raising of a free generation is desired, let us first demolish these prisons called colleges and lyceums. Socialists, let us think of the future of our children, still more than of the amelioration of our own condition. Let it not be forgotten that we ourselves, belong more to the world of the past than to the society of the future. By our education, our old ideas, our vestiges of prejudices, we are still the enemies of our own cause; the mark of the chain can yet be seen about our necks. But let us strive to save the children from the sad education that we ourselves have received; let us learn to raise them in a way that will develop them to the most perfect physical and mental health; let us learn to make such men of them as we would have desired to be ourselves.

Let us not forget that the ideal of a society is always realized. The present bourgeois society, completely represented by the State, has done for education precisely what it has desired to do. Now what does the State make of the children without family, entrusted to its charge? We know only too well: it gathers them into orphanages where, ill-nourished, ill-tended, the great majority of them succumb; then it raises the rest of these children to make of them gangsters, prison guards, detectives. That is its work and the society represented by it is fully satisfied. As for us, when our turn will come,-and come it certainly will,-when we shall be able to act and to realize our will, our great aim will be to prevent our children from undergoing all the miseries we ourselves have suffered.

Let us be firmly resolved to make free men of them, we who have not yet liberty, but only the vague hope for it.

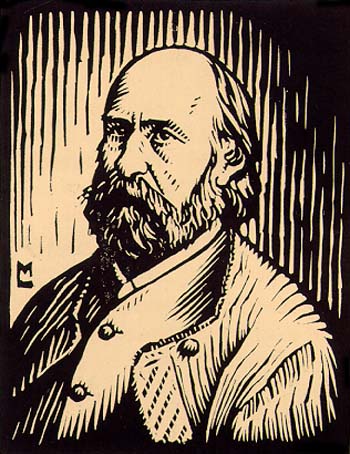

[The above article by Elisée Reclus, and the following excerpts by Elie Reclus, were first printed in LA COMMUNE, Almanach Socialiste pour 1877, Geneva, Imprimenc du Rabotnik, Montchoisy 26; now long out of print and very scarce. These two articles appear in this book for the first time in the English translation. - EDITOR.]